Author’s note: The ideas in here were buzzing around me like bees until I finally started writing them down. Then a call for proposals went around that seemed like it would be a good fit for this still-developing piece so I asked a friend if they’d like to join me, submitted a proposal and … set this aside while waiting. The proposal was rejected, the bees in my brain had quieted, the friend I was going to write with was busy with their doctoral program, and now it’s 2 years later. So I am going to let this go by posting an unfinished, unedited version online. Best case scenario, this provides food for the bees in someone else’s head!

Abstract

This article uses the vocational awe framework to examine how rhetorics of care are instrumentalized in a way that maximizes extraction and interferes with liberatory ideas of justice. Caring for ourselves and each other is a necessary part of being human. But when institutions and workplaces control the narrative, care can be extracted from us and used to manipulate us into providing unpaid labor or unsafe labor. The contradictions become especially apparent when we are attentive to the lack of urgency in addressing oppressive structures and who gets left out of our care practices. This article talks about the benefits and risks of caring and care work, to both provider and recipient. It concludes by suggesting ways we can reconsider how we show care and the power of saying no.

“What does it mean to shift our ideas of access and care (whether it’s disability, childcare, economic access, or many more) from an individual chore, an unfortunate cost of having an unfortunate body, to a collective responsibility that’s maybe even deeply joyful?

What does it mean for our movements? Our communities/fam? Ourselves and our own lived experience of disability and chronic illness?

What does it mean to wrestle with these ideas of softness and strength, vulnerability, pride, asking for help, and not—all of which are so deeply raced and classed and gendered?” (Piepzna-Samarasinha, 2018, 16)

Introduction

Vocational awe

““Vocational awe” refers to the set of ideas, values, and assumptions librarians have about themselves and the profession that result in beliefs that libraries as institutions are inherently good and sacred, and therefore beyond critique.” (Ettarh, 2018)

Care

Within library work, care has been a part of the historic process of colonizing (civilizing) subordinate populations, in a way that is inherently gendered, racialized, and classed (Ettarh, 2018; Schlesselman-Tarango, 2016). In talking about the importance of knowing our history, Zvyagintseva (2021, 14) observes that, “most individuals would rarely be opposed to care, consent, and reciprocity [but] at an institutional level, the powers of colonialism, imperialism, capitalism, patriarchy, and industrialization… make moral bonds nearly impossible to put into action, as they reduce any relationship to the logic of exchange”. She points out that within librarianship, we are often required to move locations to find jobs, which often results in moving us away from family and other community support networks. Those who can’t move, those who aren’t considered productive in this capitalist system of wage labor (e.g., disabled people excluded from the workforce for any reason), those forced to retire or retreat from the hostile conditions of working life, are severed from workplace support. While some researchers have found that librarians “routinely incorporated themselves and their colleagues explicitly into their framing of care within librarian work” (Paterson and Eva, 2022, 8), we question how accurately this describes the experiences of people on the margins, people whose racial, class, or gender identities mark them as outside the normative-yet-ambiguous circles of collegiality (Lo, Coleman & Pankl, 2022; Kendrick & Damasco, 2019). Or people who need their colleagues to do something as simple as wear a face mask during a pandemic, and have to make risk evaluations about whether to stay or leave for their own safety.

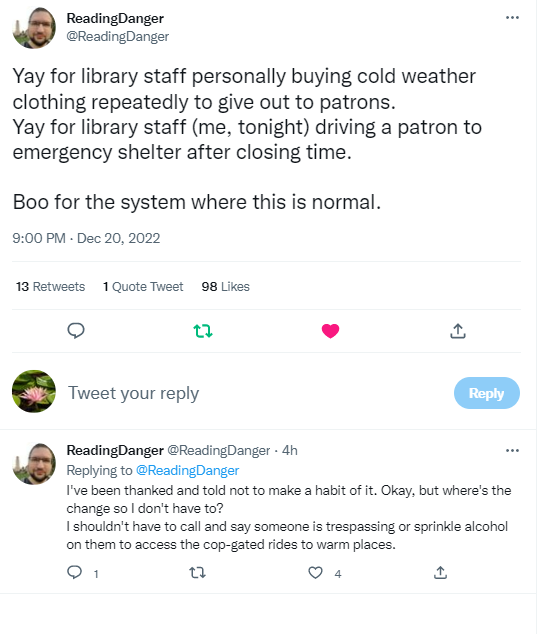

Nishida (2022, 122) “Under the racialized, ableist, and cisheteropatriarchal political economy, people’s labor capacity and its attached value are constructed and exploited as the care labor force, while their own emerging impairments and care needs are actively overlooked.” Affective relationships between care giver and care receiver can be taken advantage of by the capitalist system when, for example, librarians buy winter coats for unhoused patrons (@ReadingDanger, 2022) or help community members use online job application portals. While the ethical implications of librarians handling patrons’ financial, legal, medical, and other records in the course of our work is also up for debate (Kaun and Forsman, 2022), the focus here is on the gradual wearing out (burning out) of library workers.

Exhausting the worker, using up the worker, to plug holes in the social safety net rather than let failures of government policy destroy the person in front of us. This results in the slow death (debility) of both the care-giver and care receiver, but the professional indoctrination we receive in libraries gives us delusions of being saviors while ignoring how, by not actually acting in solidarity with care-receivers in an explicitly political sense – in the sense of advocating to change the systems in which we labor, we’re reproducing what bell hooks called white supremacist capitalist patriarchy.

Justice

Disability justice presents care as a messy, interdependent, mutually constituted part of human relationships. Rather than one person (or group of people) always being the Care Giver and a separate person a Care Receiver, rather than some people cut off from the enclosure of care and others incarcerated into that enclosure, care in the Disability Justice model is part of life.

One way that diversity models are different from justice can be seen in how diversity offices and initiatives are treated as “an enclosure into which go the demands, complaints, and stories of minoritized and marginalized people on campus and where they will remain” in a way to serves to maintain white supremacy rather than challenge it (Leung, 2022, 756-757). Diversity in this sense allows for sprinklings of those in enclosed categories to be scattered about for decoration without making structural or conceptual changes. Within diversity discourse, it’s like saying that you want to make sure that everyone has a seat at the table without acknowledging who that table belongs to–who has the power to send out or retract invitations (Collins, 2018, 47-48). Another analogy that is possibly more specific to this paper is that diversity operates by putting out statements that buses and hotels are accessible on promotional materials without acknowledging how many people that still leaves out or making any larger changes to practice.

A justice-based model, however, confronts inaccessibility as a cultural problem rather than an individualized one in which people have to request specific accommodations for their problems (for themselves as problems). A justice-based model designs conferences with the expectation of difference, with the knowledge that accessibility includes but also goes beyond ideas of individual impairment to recognizing the need to plan for people who are surveilled and policed because of their race or gender presentation (Mingus, 2011). And not just plan for the physical spaces and the sign language interpretation and the accessible handouts, though that is important, but also to plan for a space where disabled, racialized, and gender expansive people can share our stories and have them understood and valued rather than being “met with backlash, avoidance or blank faces and awkward silence because people have not done their own work to educate themselves” (Mingus, 2018). Disability justice is a transformational model built on networks of care and critique.

Within this paper, we’ll talk about the benefits of care, the hazards of care, the inherent contradictions or lies of so-called care-giving professions, and what we envision as a possible future.

Benefits of care

Even at work, we’re still people and people sometimes need to receive care and caring behavior between people can build strong communities/relationships. Librarianship is often described as a caring profession [can a profession/service orientation actually get us to a true relational model or is what we’re getting at more rightly called harm reduction?? Thinking of Jasbir Puar’s writing on debility/disability and Marta Russell’s writing on the money model]. The emotional work of exchanging care can help us feel less alone, reduce stress, and build a more supportive work environment (Schomberg, 2018). When viewed as a form of activism, care for self and others means sustainability in a disability justice sense, where we recognize the need to respect our embodied experiences so we can stay in the fight for the long haul (Sins Invalid, 2015) and are able to grow in a way that can transform power relationships (Baldivia et al., 2022).

Taking a feminist lens to this discussion brings us to Higgins’ (2017) argument for bringing the library values of social responsibility and service to the public good to the forefront of professional work. Higgins discusses how those who have traditionally had care-giving responsibilities are contributing to the well-being of society as a whole. Unless you’re a Thatcherite who doesn’t believe society exists, you should be able to think of areas in which these relational ethics have supported the development of strong bodies of constructed knowledge which emphasize collaboration and interdependence (examples range from Vygotsky to Indigenous fire keepers).

The sense of care we have described here is what Blum refers to as “[the] Heideggerian conception of care as a universal parameter… intrinsic to [humans’] mutually oriented relations” (2017, p#), which is different from the healthcare model of service, in which a (deficient) customer receives care that has been paid for by an individual or by the state. Moving care from something viewed as a human relational norm to a hierarchical (white supremacist) or capitalist (individualist, profit-driven) model is where we see many of its hazards.

Hazards of care

Rosen notes that “[as] depression and anxiety have become keywords for academia and the professoriate, care is becoming a keyword for librarianship and library workers… [but the] professional history of the librarian is such that we are always the caretaker, never the cared for” (2022). However, as Piepzna-Samarasinha (2018, 18) notes, “Some of us fear that letting anyone in to care for us will mean we are declared incompetent and lose our civil rights…. Some of us know that accepting care means accepting queerphobia, transphobia, fatphobia or sexphobia from our care attendants”.

We also have to confront gendered and racialized expectations about who provides care and how. In her exploration of the gendered aspects of affective labor in academic libraries, Sloniowski notes that “emotional labor and care work is not valorized as highly as intellectual immaterial labor [and] the dissolving boundaries between the productive and reproductive sphere reinscribe all manner of exploitation and oppression of women. [Additionally] affective labor and care work are increasingly delegated to racialized migrant communities” (2016, 654).

Using the vocational awe framework we can see how care can become or perpetuate saviorism, colonization, white supremacy. Factor in a care-needer who violates community standards by being (in a white supremacist society) a person with darker skin, queer/trans, visibly disabled or sick, etc. and we get disgust and eugenics (“ugly” laws, forced sterilization, criminalization/medical pathologization) promoted as “care” (Ettarh, 2018; Schomberg and Highby, 2020).

But let us follow the example of Arellano-Douglas (2020) and take a step outside libraries, to see if we can look at these hazards from a broader perspective of another majority-female-but-not-feminist, care-giving profession: healthcare.

Care and caregiving within gerontology have been theorized as social problems with the focus on finding practical solutions. Social gerontology theories in some cases also situate a person who both receives care and provides care as a problem to be solved rather than as an indication of interdependence and positive social relations. This expectation of unidirectional power “leaves intact the institutionalization of disempowerment and dependency that are central to the medical model of caring, securing the cared-for in a position of passivity and objectified helplessness and the carer in a position of authority and power” (Danneferet al., 2008). Also, presenting people who receive care as passive bodies in that relationship ignores how they “are engaged in generative action that sustains their own being and that of others” (Danneferet al., 2008).

In another healthcare profession, this time in the context of nursing, Mohr (1999) points out that decontextual, deficit-model interventions, along with the conflicting ideologies and agendas of health care workers and administrators, often work to discount the actual realities and needs of patients. While this article is specific to care-receivers, its discussion of the structures and processes of who gets care, who makes care decisions, whose culture is centered,and other considerations in many ways parallels the infrastructure of libraries.

To rephrase, the problems we observe in this paper are not limited to librarianship. In fact, we argue that libraries face similar obstacles as healthcare, which Nishida (2022, 108) describes as “one of the areas where the phenomenon of slow death manifests and is enforced, as those who are situated as care workers and care recipients both are exploited and experience mutual deterioration”.

Contradictions of care

What we say versus what we do

Saying the librarianship is a caring profession, saying that we need to look out for each other and advocate for labor rights ($5 a day hotel stay is a recurring conference mantra on twitter) then not wearing masks during a pandemic despite poor and racialized people who work at places like hotels and restaurants being most likely to die from covid, even more likely than unvaccinated white people. ( Parallels between this and institutional DEI statements/goals? abolition?)

- “Disability scholars and activists have exposed the public rhetorics and private dynamics in which care (and cure) can function as a harmful narrative, a form of coercion, or a screen for real violence.” (Rosen 2022)

- “Caretaking… can be escapist, avoidant, compulsive, a coping mechanism to get outside what is unbearable within the self.” (Rosen 2022)

- “in cultures of white womanhood we are often taught that our compassion is, in itself, a meaningful political act, and a sufficient one. And we are often taught that our compassion, knowledge, or help is needed and indeed desired by certain others.” (Rosen 2022)

Transactional versus reciprocal

When talking about receiving care, in a medical sense, the options are either to get support from (unpaid) friends and family or to receive state services. In discussing unpaid care, Piepzna-Samarasinha (2018, 21) notes how nondisabled people expect that care needs will be short-lived. A broken leg, a treatable cancer, a pregnancy. The event causing a care need is an emergency and people respond with a sense of urgency (classic white supremacy culture if you listen to Okun, 2021). What people don’t do is build in capacity for sustainability; those with chronic illness and lifelong care needs need not apply. The responses in the latter case take you through the “faker or not” gauntlet. The territory of spoiled identities and surplus population.

And there we get hired care-givers. Jasbir Puar (2017) notes that those privileged enough to get state recognition of having an illness or disability that requires care (which often excludes care workers from the Global South and other members of minoritized groups) become products (profits) for the medical industrial complex. Those who don’t qualify for state support or who don’t have robust health insurance do so as well, while they also become ever more tightly confined within an enclosure of debt. Those recognized by the state get to claim disability identity and may have the chance to rehabilitate their own spoiled identities by reproducing the idea that disability is abnormal, a “discrete minority” (Snyder and Mitchell, 2010). Everyone else who needs care but falls outside these bounds of normalcy? Anyone who needs others to wear masks during a global pandemic? Surplus population.

Bringing this back to library work gives us the opportunity to more critically examine our history and the stories we tell about ourselves as a field. As Zvyagintseva (2021) notes, we exchange our labor for wages within a larger system of “individual property relations rather than ethics of care, reciprocity, and the commons” (p.4). This is not a critique of any individual who needs to work to earn money to live. This is an acknowledgement that we are actors within a society that may or may not operate the way we wish it to. Even the work we do to care for ourselves and our families can be co-opted within this system, “greasing … the machinery of capitalism in order to create new workers as well as make existing workers more productive” (p.11).

So how do we go from this transactional, neoliberal model of care to something else? In discussing what she calls affective collectivity, Nishida (2022, 104) describes building emotional relationships and solidarity between care workers and care receivers despite prohibitions from employers (due to a stated fear of liability). In this scenario, building relationships between care giver and care receiver is an act of resistance to structural divisions that are also reinforced by the racialized, gendered, and citizenship status of those on either side of this divide. It is also an act of resistance to the understanding that care givers and receivers are nothing more than passive victims of a neoliberal state.

Maintaining versus challenging oppression

- Management models built on plantation logics that demonstrate a hierarchy of value, maximizing efficiencies (exploitation), social relationships continue to influence workplaces in industrial and post-industrial societies, including library workplaces (Rosenthal, 2018; Zvyagintseva, 2021, 17)

- “the leader must resist the hubris of expertise and pedantry that can materialize in conceptions of customer care or service delivery” (Blum, 2017)

- “Ettarh’s influential work on “vocational awe” gathers together lines of thought that question the ways in which care work in librarianship can occlude racialized power dynamics that place librarians (figured as nice white ladies) above the “community” that they serve and ultimately save. She reviews the historical discourses linking the library to the sanctuary, and shows that these deeply rooted archetypes not only overdetermine the ways in which we engage with patrons—limiting the possibility of a “more reciprocal, respectful, and responsible relationship”21—but also affect the ways we largely do not hold our institutions accountable for conditions that might better sustain our work and minds and bodies. The result is that care work in librarianship is, in most cases, narrowly aligned with something “we” do for “our patrons,” and which ultimately accrues power back to us” (Rosen 2022)

Envisioning a future of care

“Talk helps people consider the possibilities open for social change…. One person said, ‘freedom is an endless meeting.’” (Students for a Democratic Society member, 1965, as cited by Polletta, 2002).

We need historical and futurist counter-narratives to encourage radical dreaming and re-thinking of what’s possible. We need to make librarianship explicitly political, grounded in the historical realities of a multiplicity of people. If we want a profession that truly incorporates an ethic of care into its work, we need to recognize the work we do as work rather than allowing vocational awe to delude us. We need to be attentive to rhetoric and relationships and material realities. As Zvyagintseva (2021, p.18) suggests, we need to embrace the caring possibilities that come with refusal: sabotage, slowdowns, and labor strikes are forms of caring for ourselves and our fellows who are struggling to survive. Presenting these actions as mindless destruction is part of a practice to strip labor rights from their historical context, to depoliticize long histories of intersections between classism, racism, and ableism.

We also need to respect our own bodyminds. Our pain, fatigue, guilt and anger at the social inequities we experience and witness are important pieces of affective information. When we respect these feelings as part of our personal and collective knowledge we build the potential to engage in affirmation and resistance (Nishida, 2022; Obourn, 2020).

- “glorification of concrete outputs in performance measurements over emotional labor as an example of the ways in which care work is devalorized in relation to other tasks” (Sloniowski, 2016, 658) AND “There is a ceiling for care workers in the university because we are viewed not as professionals or scholars, but as support and administrative workers. This perception remains despite our faculty status in most universities. However, the work we do is central to the production of knowledge.” (Sloniowski, 2016, 660) — (is there any way to valorize care work in this setting without it again reproducing the systems of oppression we’re trying to work against??)

- In a profession that is literally built on caring, we still have much to learn about creating conditions that support the wellbeing, and care about the survival, of many of us. (Rosen, 2022)

- Borders between community vs library vs library worker? Reminder that library workers are part of their communities? These boundaries seem policed to an extent that suggests that they are highly artificial and about reinforcing hierarchies, but also skill development is helpful (I don’t think these ideas are in conflict but would need to be fleshed out)

Citations

Arellano Douglas, V. (2020). Moving from critical assessment to assessment as care. Communications in Information Literacy, 14 (1), 46-65. https://doi.org/10.15760/comminfolit.2020.14.1.4

Baldivia, S., Saulat, Z. and Hursch, C. (2022). Creating more possibilities: Emergent strategy as a transformative self-care framework for library EDIA work. In Brissett, A. and Moronta, D. (Eds.). Practicing Social Justice in Libraries, 133-144. Routledge.

Blum, A. (2017). Introduction: The dialectic of care. In Alan Blum and Stuart J. Murray (Eds.). The Ethics of Care: Moral Knowledge, Communication, and the Art of Caregiving, p. 1-24. Routledge.

Brown, D. N. and Settoducato, L. (2019). Caring for your community of practice: Collective responses to burnout. LOEX proceedings, 43-47. https://commons.emich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1016&context=loexconf2019

Dannefer, D., Stein, P., Siders, R., & Patterson, R. S. (2008). Is that all there is? The concept of care and the dialectic of critique. Journal of Aging Studies, 22(2), 101–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2007.12.017

Ettarh, F. (2018, Jan. 10). Vocational awe and librarianship: The lies we tell ourselves. In the Library with the Lead Pipe. https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2018/vocational-awe/

George, K. (2020). DisService: Disabled library staff and service expectations. In Veronica Arellano Douglas and Joanna Gadsby (Eds.). Deconstructing Service in Libraries: Intersections of Identities and Expectations, 96-123. Litwin Press. https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1681&context=lib_articles

Higgins, S. (2017, November 10). Embracing the feminization of librarianship. In Feminists Among Us. https://doi.org/10.31229/osf.io/q6zbw

Kaun, A., & Forsman, M. (2022). Digital care work at public libraries: Making Digital First possible. New Media & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221104234

Kendrick, K. D., & Damasco, I. T. (2019). Low Morale in Ethnic and Racial Minority Academic Librarians: An Experiential Study. Library Trends, 68(2), 174–212. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2019.0036

Lo, L. S., Coleman, J., & Pankl, L. (2022). Collegiality and tenure: Results of a national survey of academic librarians. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 48(6). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2022.102589

Mingus, M. (2018, 3 November). Disability justice is just another term for love. Leaving Evidence [blog] https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2018/11/03/disability-justice-is-simply-another-term-for-love/

Mingus, M. (2011, 12 February). Changing the framework: Disability justice. Leaving Evidence [blog] https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2011/02/12/changing-the-framework-disability-justice/

Mohr, W. K. (1999). Discovering a dialectic of care. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 21(2), 225–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/01939459922043857

Nishida, A. (2022). Just Care: Messy Entanglements of Disability, Dependency, and Desire. Temple University Press.

Paterson, A. M., & Eva, N. (2022). “Relationships of Care”: Care and Meaning in Canadian Academic Librarian Work during COVID-19. Partnership: The Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research, 17(2), 1-26. https://journal.lib.uoguelph.ca/index.php/perj/article/download/7055/6741

Piepzna-Samarasinha, L. L. (2018). Care Work : Dreaming Disability Justice. Arsenal Pulp Press.

Polletta, F. (2002). Freedom is an Endless Meeting: Democracy in American Social Movements. University of Chicago Press.

Puar, J. K. (2017). The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability. Duke University Press.

Rosen, S. S. (2021). Caring work: Reflections on care and librarianship. In Miranda Dube and Carrie Wade (Eds.). LIS Interrupted: Intersections of Mental Illness and Library Work,203–17. Sacramento, CA: Library Juice Press. https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/168210/Rosen–Caring-Work.pdf?sequence=1

Rosenthal, C. (2018). Accounting for Slavery: Masters and Management. Harvard University Press.

Schlesselman-Tarango, G. (2016). The legacy of Lady Bountiful: White women in the library. Library Trends, 64(4), 667-686. https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/items/97371

Schomberg, J. & Highby, W. (2020). Beyond Accommodation: Creating an Inclusive Workplace for Disabled Library Workers. Library Juice Press.

Schomberg, J. (2018). Disability at work: Libraries, built to exclude. In Nicholson, K.P. and Seale, M. (Eds.). The Politics of Theory and the Practice of Critical Librarianship, 115-127. Library Juice Press.

Sins Invalid. (2015). The Ten Principles of Disability Justice. https://sinsinvalid.org/10-principles-of-disability-justice/

Sloniowski, L. (2016). Affective labor, resistance, and the academic librarian. Library Trends 64(4), 645-666. doi:10.1353/lib.2016.0013.

Snyder, S.L., & Mitchell, D.T. (2010). Introduction: Ablenationalism and the Geo-Politics of Disability. Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies 4(2), 113-125. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/390394.

Zvyagintseva, L. (2021). Articulating our very unfreedom: The impossibility of refusal in the contemporary academy. Canadian Journal of Librarianship, 7, 1-24. https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/cjalib/2021-v7-cjalib06146/1084793ar/

Leave a comment